The Piano Factory

Today Harmonic Analysis Diary takes on a sonatina by a composer who's usually crammed down among the footnotes- Muzio Clementi.

Clementi, along with Telemann and John FIeld, is among the composers who got screwed by the Great Man Theory of music. These men were talented, prolific, successful composers, but (alas) you can only fit so many pages in the music history textbook and, as a result, Bach, Mozart, Beethoven and the other huge names get top-billing and, over centuries, an inertia whereby they now seem more like deities than artists in the public conception.

(I feel that the media revolution of the past decade - the arrival of the internet, the sudden ubiquity of digital recordings and digital media -- is gradually undoing this injustice, slowly but surely exhuming masterworks that wouldn't have had a chance twenty years ago. Nobody is going to knock Bach off his pedestal, of course, but future generations will be only a few mouseclicks from juding for themselves whether Pachelbel's work deserves footnote status).

Anyway, Clementi was a superstar of his day. He bested Mozart in piano competitions (just think: somebody at that concert undoubtedly yawned and wished Mozart and Clementi would hurry up), wrote reams of music (much admired by Beethoven), started a piano factory, worked as a music publisher (put out the first English editions of Beethoven's sonatas, for instance), tore trees in half with his bare hands, taught a bear to play chess, etc etc.

His music is, moreover, the purest distillation of the 'classical' style I can imagine, so much so that it borders on caricature at times. Whereas Haydn and Mozart liked surprise and private harmonic cleverness, Clementi usually preferred an unbroken hum of elegance and exquisite filagree. This is not to denigrate his work- I am sure most unbiased listeners would find his piano sonatas the equal of those of Haydn and Mozart, albeit much more conservative.

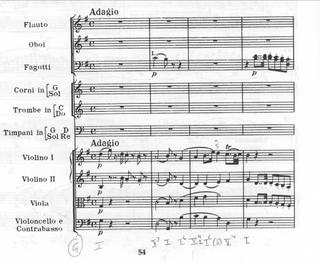

DeVoto serves up Clementi's:

Sonatina in D Major, Op. 36, No, 6 (1787)

as an apertif before a passel of Mozart works. The piece is a little thing, just two movements, and technically challenging only for people who suck at the piano (i.e. me).

The first movement, Allegro con spirito, is as tidy a sonata form as you could find, as pruned and symmetrical as the gardening in Regent's Park. (Please excuse me if that analogy seems forced, but the neat rows of ruthlessly-pruned geraniums really do evoke a similar level of rigor and geometry). Schematically:

Theme A, transition (modulates), Theme B (repeat to top), Development (modulates to subdominant, then back to tonic), Recapitulation (Theme B in tonic now, yawn), End (repeat from Development if so inclined).

If this seems dry, you should hear it. You can practically see the gears clicking into place as Theme B arrives right on schedule or the harmony goes just far enough afield in the Development to constitute having been a Chromatic Episode. However, this rather harsh view misses the point- the audience in Clementi's day presumably didn't mind the form because it was just a vehicle for the music. It probably wouldn't have occured to them to find it dull anymore than we question the rigid panel format of a Doonesbury comic strip.

So, what does it sound like? For the most part, the right hand plays elegant classical melodies, sparkling runs and scales in thirds while the left hand chugs along in a variety of classical accompanimental patterns. (Unfortunately, it's hard to get away from words like 'elegant' 'sparking' and 'charming' when writing about this stuff.) The sonatina really is almost a textbook for Kinds of Classical Piano Accompaniments, and the change of accompaniments patterns is a key feature that separates, say, the Development from Theme A in the mind of the listener. I should note, too, that Clementi is tasteful in the way he uses these accompaniments- a case in point is in measure 4, where he momentarily varies the outline of the Alberti pattern to avoid parallel octaves and, I would say, just provide a little variety. Moreover, the clarity of the resulting texture - it's often basically two-voices - has an soothing, graceful quality. ("Graceful", too, gets old fast.) There's very little of the muddy churning that composers like Beethoven deploy for drama.

Harmonically, there's not much to say. I, ii6, IV, V, etc. (all the primary ingredients of the classical common practice) obediently thump away beneath the melody. Clementi does use pedal tones, though, in a way that is exciting, effective, and wholly idiomatic. The chromatic episode in the development is pretty standard: fully dimished 7th chords that serve the dual purpose of creating some turmoil while giving Clementi an EZ-Pass card to the subdominant, the whole passage enriched with anticipations and apoggiatura figures.

The second movement, Allegretto spiritoso, is a lot more interesting from an analysis standpoint. Schematically, it's a simple ternary form A (fine) B (da capo), but the lack of rigidity seems to let Clementi create something much more playful.

Whereas the first movement was the stodgiest 4/4, the Allegretto glides from foot to foot in a version of 6/8 that feels like 2+1+2+1. The pristine, balanced phrases of the first movement are abandoned for short, motivic phrases that enchain from one another, the tail of one acting as the head of the next. Even the rigid right hand/left hand independence of the first movement is softened now, the right hand's melody often seeming to have less importance than the left hand's accompanimental commentary. In short, this is a movement about rhythm and gesture rather than tunes.

In terms of harmony, this movement is interesting because Clementi is less dependent on accompaniments that outline a chord (though they do crop up). As a result, there is a greater degree of harmonic ambiguity, and the interest comes from the motivic energy and variations in the thickness of the texture. Indeed, the entire A section is almost a sort of developing variation, gradually embellishing the skeletal melody with runs and thirds until it finally launches into a bombastic churn as it charges the finish line. ("Churn" is also on the list.)

At first, the B section seems radically simpler - it uses more standard accompaniment figures - but it soon becomes apparent that, rather than a simple contrast to A, B is being used as a sort of development. Clementi takes the motives of A and spins them out (rather than simply embellishing them as he does progressively in A). He explores the bombastic churn in an extended minor key pedal tone episode and then, for contrast, takes the motives and puts them through their paces in a dainty, unvaried two-voice texture. All of this builds to a flashy scale passage that cutely hints at the da capo return to the tonic by shoehorning a flattened seventh scale degree into the upward scale.

Next post: Mozart arrives.

Also, feel free to check out the new corollary to this diary at naturalharmonics.blogspot.com, in which I talk about music much less formally.

Clementi, along with Telemann and John FIeld, is among the composers who got screwed by the Great Man Theory of music. These men were talented, prolific, successful composers, but (alas) you can only fit so many pages in the music history textbook and, as a result, Bach, Mozart, Beethoven and the other huge names get top-billing and, over centuries, an inertia whereby they now seem more like deities than artists in the public conception.

(I feel that the media revolution of the past decade - the arrival of the internet, the sudden ubiquity of digital recordings and digital media -- is gradually undoing this injustice, slowly but surely exhuming masterworks that wouldn't have had a chance twenty years ago. Nobody is going to knock Bach off his pedestal, of course, but future generations will be only a few mouseclicks from juding for themselves whether Pachelbel's work deserves footnote status).

Anyway, Clementi was a superstar of his day. He bested Mozart in piano competitions (just think: somebody at that concert undoubtedly yawned and wished Mozart and Clementi would hurry up), wrote reams of music (much admired by Beethoven), started a piano factory, worked as a music publisher (put out the first English editions of Beethoven's sonatas, for instance), tore trees in half with his bare hands, taught a bear to play chess, etc etc.

His music is, moreover, the purest distillation of the 'classical' style I can imagine, so much so that it borders on caricature at times. Whereas Haydn and Mozart liked surprise and private harmonic cleverness, Clementi usually preferred an unbroken hum of elegance and exquisite filagree. This is not to denigrate his work- I am sure most unbiased listeners would find his piano sonatas the equal of those of Haydn and Mozart, albeit much more conservative.

DeVoto serves up Clementi's:

Sonatina in D Major, Op. 36, No, 6 (1787)

as an apertif before a passel of Mozart works. The piece is a little thing, just two movements, and technically challenging only for people who suck at the piano (i.e. me).

The first movement, Allegro con spirito, is as tidy a sonata form as you could find, as pruned and symmetrical as the gardening in Regent's Park. (Please excuse me if that analogy seems forced, but the neat rows of ruthlessly-pruned geraniums really do evoke a similar level of rigor and geometry). Schematically:

Theme A, transition (modulates), Theme B (repeat to top), Development (modulates to subdominant, then back to tonic), Recapitulation (Theme B in tonic now, yawn), End (repeat from Development if so inclined).

If this seems dry, you should hear it. You can practically see the gears clicking into place as Theme B arrives right on schedule or the harmony goes just far enough afield in the Development to constitute having been a Chromatic Episode. However, this rather harsh view misses the point- the audience in Clementi's day presumably didn't mind the form because it was just a vehicle for the music. It probably wouldn't have occured to them to find it dull anymore than we question the rigid panel format of a Doonesbury comic strip.

So, what does it sound like? For the most part, the right hand plays elegant classical melodies, sparkling runs and scales in thirds while the left hand chugs along in a variety of classical accompanimental patterns. (Unfortunately, it's hard to get away from words like 'elegant' 'sparking' and 'charming' when writing about this stuff.) The sonatina really is almost a textbook for Kinds of Classical Piano Accompaniments, and the change of accompaniments patterns is a key feature that separates, say, the Development from Theme A in the mind of the listener. I should note, too, that Clementi is tasteful in the way he uses these accompaniments- a case in point is in measure 4, where he momentarily varies the outline of the Alberti pattern to avoid parallel octaves and, I would say, just provide a little variety. Moreover, the clarity of the resulting texture - it's often basically two-voices - has an soothing, graceful quality. ("Graceful", too, gets old fast.) There's very little of the muddy churning that composers like Beethoven deploy for drama.

Harmonically, there's not much to say. I, ii6, IV, V, etc. (all the primary ingredients of the classical common practice) obediently thump away beneath the melody. Clementi does use pedal tones, though, in a way that is exciting, effective, and wholly idiomatic. The chromatic episode in the development is pretty standard: fully dimished 7th chords that serve the dual purpose of creating some turmoil while giving Clementi an EZ-Pass card to the subdominant, the whole passage enriched with anticipations and apoggiatura figures.

The second movement, Allegretto spiritoso, is a lot more interesting from an analysis standpoint. Schematically, it's a simple ternary form A (fine) B (da capo), but the lack of rigidity seems to let Clementi create something much more playful.

Whereas the first movement was the stodgiest 4/4, the Allegretto glides from foot to foot in a version of 6/8 that feels like 2+1+2+1. The pristine, balanced phrases of the first movement are abandoned for short, motivic phrases that enchain from one another, the tail of one acting as the head of the next. Even the rigid right hand/left hand independence of the first movement is softened now, the right hand's melody often seeming to have less importance than the left hand's accompanimental commentary. In short, this is a movement about rhythm and gesture rather than tunes.

In terms of harmony, this movement is interesting because Clementi is less dependent on accompaniments that outline a chord (though they do crop up). As a result, there is a greater degree of harmonic ambiguity, and the interest comes from the motivic energy and variations in the thickness of the texture. Indeed, the entire A section is almost a sort of developing variation, gradually embellishing the skeletal melody with runs and thirds until it finally launches into a bombastic churn as it charges the finish line. ("Churn" is also on the list.)

At first, the B section seems radically simpler - it uses more standard accompaniment figures - but it soon becomes apparent that, rather than a simple contrast to A, B is being used as a sort of development. Clementi takes the motives of A and spins them out (rather than simply embellishing them as he does progressively in A). He explores the bombastic churn in an extended minor key pedal tone episode and then, for contrast, takes the motives and puts them through their paces in a dainty, unvaried two-voice texture. All of this builds to a flashy scale passage that cutely hints at the da capo return to the tonic by shoehorning a flattened seventh scale degree into the upward scale.

Next post: Mozart arrives.

Also, feel free to check out the new corollary to this diary at naturalharmonics.blogspot.com, in which I talk about music much less formally.